What's in a Name?

The power of diagnosis - for good and for ill.

“What’s in a name? That which we call a rose

By any other name would smell as sweet.”

-Romeo & Juliet

“Oh jeez, this one’s going to suck.”

I was on my 2nd rotation of medical school, working in the hospital. The residents were going down the list of new patients admitted overnight, splitting them up based on complexity.

When it came time to sort this particular patient, there was a noted disinterest.

It wasn’t the complexity: we were used to that as the level 1 trauma hospital in the area. Long problem lists were the norm.

It wasn’t the rarity of the diagnosis: we savored those as learning opportunities.

It wasn’t the patient: we hadn’t met her yet.

It was the diagnosis itself that drew the sighs.

.

.

.

The Power of Diagnosis

So much of what I enjoy about this blog is that it gives me space to “muse” as my friend DeAndre told me recently.

I'd like to muse with you today about the power of diagnosis.

Since I spend more time with my patients as a DPC (direct primary care) doctor, I’m not uncommonly making diagnoses for patients who are quite complex or have been suffering for years without a diagnosis. This isn’t to say I’m particularly brilliant in some way, I just have the advantage of time many doctors do not yet have.

Sometimes the diagnosis is met with tears of joy at finally having a valid “reason” for the suffering. Other times, the patient overidentifies with the diagnosis***, perhaps causing unintentional harm.

From a clinical perspective, a diagnosis may help or harm a patient. A diagnosis can offer a more focused direction for treatment, which can be helpful. However, it can also result in anchoring bias, preventing us from considering a broader differential or alternative diagnoses when indicated.

Diagnoses are not only for clinicians. Insurance companies - health, life, and disability insurance in particular - may approve or deny coverage based on a diagnosis. Jobs may be denied based on a diagnosis (e.g., military service).

So diagnoses are important for the patient, the physician, and outside parties, and there are negative consequences to manage with making a diagnosis as well. How do we maximize the benefits while reducing the risks of diagnosis as much as possible?

.

.

.

Making the Diagnosis

What is required to make a diagnosis?

1. Authority

Not everyone can make a diagnosis. In fact, people can get in hot water when they try to make a diagnosis without the proper authority (i.e., posing as a physician). Generally, licensed professionals are the one making a diagnosis; however, there’s been some debate about the ability of other healthcare practitioners to diagnose and treat patients.

In Ohio, pharmacists currently do not have diagnostic authority. Ohio Senate Bill 230, introduced in July 2025, would allow pharmacists to test for and treat certain respiratory conditions like colds, flu, and strep throat, essentially giving them diagnostic authority based on test results. [Giving diagnostic authority to people not trained in diagnosis - what could possibly go wrong? I’ll save this soapbox for another blog.]

So that’s the technical side of authority.

There’s also the perspective of authority in the eyes of the patient. Patients may seek a second opinion when they do not feel or believe the first physician has the knowledge or authority to make the diagnosis. This is partly the art of medicine and partly expertise. We might consider it the “softer” side of diagnostic authority.

2. Knowledge & Reasoning

In order to make a diagnosis, knowledge of both the patient and the illness is required. This is what makes family physicians particularly unique: we specialize in knowing the patient. Not in a body part or surgical technique or piece of technology. We specialize in the person in front of us and knowing their long-term medical history, their values, their personality, their goals in life.

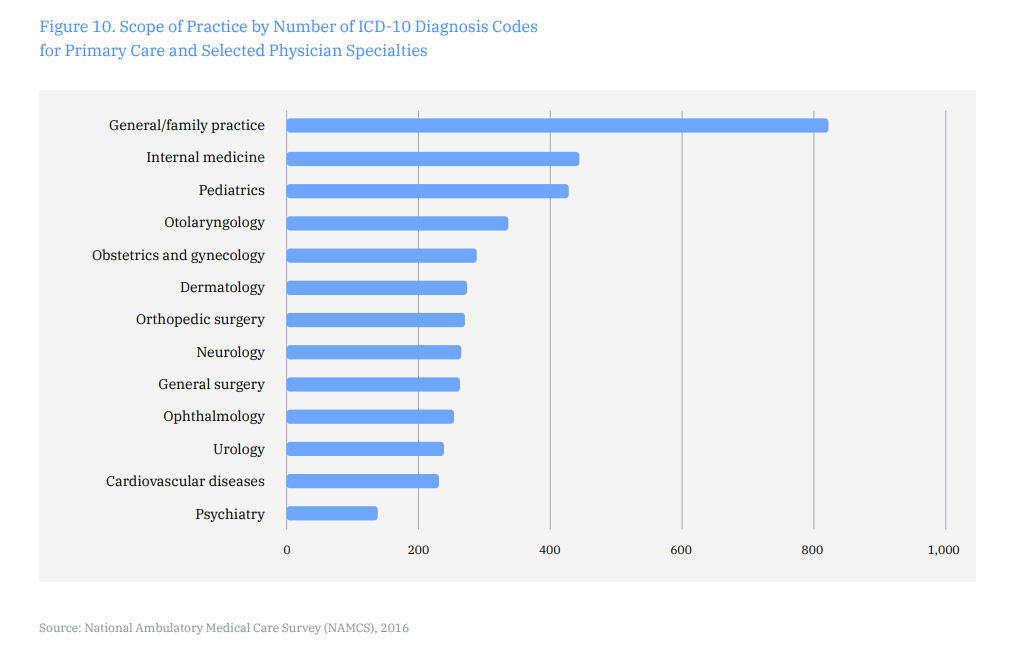

Many diagnoses require knowledge of on-going symptoms over time. This aspect of continuity in primary care lends itself to making diagnoses. In fact, family physicians make the most diagnoses compared to any other specialty (see figure below).

Knowledge of illness scripts, probabilities of test results, and differential diagnoses also aid in making a final, accurate diagnosis, among other aspects of clinical reasoning.

3. Information

The path to diagnosis involves gathering information to inform 1) the differential diagnosis which eventually leads to 2) a final working diagnosis. The differential diagnosis is a working list of all possible diagnoses for a patient’s concern.

The differential diagnosis begins the moment the patient reports a symptom and the information gathering process begins. This includes the history, physical exam, and any test results. [Shoutout to Dr. Skip Leeds of Wright State Boonshoft School of Medicine fame who has done some phenomenal work in the area of teaching how to develop a differential diagnosis.]

It is also worth noting that a test result is not a diagnosis. Every test carries with it a sensitivity and specificity (or, if we’re actually applying Bayesian statistics, likelihood ratios). The test result informs the differential diagnosis. A positive strep test may make strep more likely, but it doesn’t necessarily make it the final or only diagnosis for a patient. Additional information such as the patient’s history (e.g., they may be a strep carrier), exposures (e.g., daycare), symptoms, physical exam findings, and other test results inform the differential and final working diagnosis. It is dangerous to solely focus on one test result for diagnosis.

4. Time

Varying amounts of time are necessary for making an accurate diagnosis depending on the complexity and ramifications of the diagnosis involved. We need time to gather knowledge of the patient and the illness. This is where continuity (or knowledge of the patient over time) feels almost like cheating.

5. Benefit

There must be some level of perceived benefit by the physician and patient to make a diagnosis. For example, we don’t go to great lengths to diagnose a specific type of cold (e.g., upper respiratory infection secondary to respiratory syncytial virus (RSV)) unless there’s a benefit to making the diagnosis to guide treatment. For a newborn with a fever, diagnosing the cause as RSV versus meningitis is important because the treatment is vastly different and time sensitive. For an otherwise healthy adult, we’ll probably just call this collection of symptoms an “upper respiratory infection secondary to suspected virus”. Diagnosing it in more detail as being caused by RSV through additional testing likely isn’t helpful. Many of these patients don’t even come to a doctor to receive this diagnosis because of the perceived lack of benefit (i.e., the patient can treat the symptoms at home on their own).

.

.

.

Downsides of Diagnosis

We don’t talk about the downsides of a diagnosis enough. Sure, there’s the obvious example of a cancer diagnosis that comes with psychological ramifications. But here I’d like to consider the impact of the everyday, chronic conditions we diagnose in the clinic.

Overidentification & Illness Anxiety

One downside in particular is the over-identification of a patient with the diagnosis. The patient no longer “has” a diagnosis, but they “are” the diagnosis. This may also be referred to as “diagnostic engulfment” and can be a cause of illness anxiety.

There is a relationship between diagnostic engulfment and negative health-related outcomes. On the other hand, some amount of acceptance of a diagnosis is associated with improved patient outcomes. Unfortunately, little research has been focused on the topic of overidentification and it’s subsequent impact on a patient or ways of reducing its potential harm.

There are some objective tools to assess for this; however, as with most psychiatric conditions, the assessment of overidentification is more subjective in nature. Such an assessment should take into account not only our own impressions of the patient’s experience, but the patient’s experience as well.

This is an area I’ve been particularly interested in understanding better, so I’ll write another separate blog on this topic to dive deeper on the research that does exist.

Introduction of Bias

As a medical student, I was deployed more than once to spend time talking with the “difficult” patients. The medical team needed more details to care for these patients but, for whatever reason, the patients were unwilling or unable to give that information in a team setting or with the physicians. This is a fairly common role for medical students to play on the team - that of information-gatherer.

One particular patient had a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder in her chart. Before we even met her, I could feel the reluctance of the team to care for her. Just by knowing her diagnosis, bias had been introduced into our interaction and care for her.

Some diagnoses obviously draw more associated bias than others, and it is good to be aware of our own biases. We are human at the end of the day, and the goal isn’t necessarily to prevent any bias, but to be aware of it and to reduce its negative effect on our interactions with patients.

As mentioned earlier, a diagnosis may also introduce bias by anchoring or early satisficing on a diagnosis, preventing the full consideration of additional or alternative diagnoses.

.

.

.

Benefits of Diagnosis

This point is more straightforward, so I won’t belabor it. A diagnosis provides direction for treatment, validation for the patient, and serves an administrative role to outside parties ( for good and for ill; e.g., insurance authorization, disability benefits, etc.).

.

.

.

Optimizing the Pros & Minimizing the Cons of Diagnosis

While we may not be able to fully prevent overidentification, the introduction of bias or medical exclusions as a result of a diagnosis, we may be able to reduce harm through several avenues, such as the art of how we offer a diagnosis, making more accurate diagnoses, and the personal knowledge of a patient.

A young villager leaves her home to study medicine in the city. After years of rigorous training, she returns as a medical doctor with funds of scientific knowledge ready to help her village. The village healer greets her and says, “Now that you’ve learned to treat disease, it’s time to learn how to heal disease.”

-Original source unknown/a story from my friend

Offering a Diagnosis

I’ve been appreciating this story more and more as I progress in my career. There are technical aspects to making a diagnosis well. There’s also an art to offering a diagnosis to the patient. I’ll be spending some of my CME time this year diving into the latter through noetic medicine, which has its roots in clinical hypnosis. Others have enjoyed neurolinguistic programming as a helpful paradigm, which I may dive into more as well.

One small way I have begun to practice this already is to consciously not play God. I never tell patients “You will only live X more years.” I offer statistics about how long the average person with that condition has lived, but I am always quick to note the percentage that lived beyond the average - and that the patient may very well fall into that outlier. I’m not God, so who’s to really say how long that person will live? It’s important to share what we do know about the statistics, but so often I’ve found physicians think that means leaving out the more hopeful statistics of the outliers as well. There’s always room for hope, and it’s important to leave a seat at the table for it. The goal is to provide information that empowers the patient to make decisions that align with their own health and life goals. Not to play God.

Making a Diagnosis

Entire books have been written on the process of making a diagnosis, but suffice it to say that making an accurate diagnosis is an important step to optimizing benefits and reducing harm. It is critical to know when an algorithm applies - and when it does not. Metacognitive techniques in particular may be employed to reduce bias in the diagnostic process.

Patient Knowledge

Knowledge of a patient’s values, goals, and dreams, and a good doctor-patient relationship are key to deciding the what and how of delivering a diagnosis in an empowering way. We can also use this knowledge to design a plan with the patient that benefits their health without compromising their identity. More to come on the identity piece of this later.

.

.

.

A diagnosis: one word with quite a bit of power - for good and for ill. Ultimately, a diagnosis is the patient’s. Our role is to make and deliver the diagnosis in a way that first does no harm and serves to benefit the patient’s health.

We can do this through accurate diagnoses, thoughtfully delivered, in the context of relationship.

.

.

.

Dr. Hans Duvefelt and I collaborated on this topic to bring you an early and late career prescriptive. Read his blog here:

Trauma surgeon here - I subscribed!

Lily, this was a cliffhanger. What was the diagnosis that caused the residents’ disinterest?